Family Lines Sketched in the Portrait of Lev Landau

DOI: 10.1063/1.1688070

In this brief memoir, I shall try to describe academician Lev Davidovich Landau; his parents, Lyubov Veniaminovna Harkavi-Landau and David Lvovich Landau (my grandparents); his sister Sofia Davidovna Landau (my mother); and my association with him and our encounters in various periods of our lives.

My earliest memories of Dau (as Landau was known to those close to him) date back to 1937, when I was four years old. Into the quiet and calm of our home burst, unexpectedly, a strange kind of person. He brought an atmosphere of bustle, festivity, noisy and lengthy arguments, excitement, and shouting. Mom said that this was my Uncle Lyova [his familiar name], her brother, and that he had just arrived in Leningrad. He was very tall (especially from my four-year-old’s perspective), very thin, very disheveled, and very lively. He couldn’t stay in one spot for a second; he kept measuring our modest-sized room with his long legs, running back and forth. Not knowing what to talk to me about, he bent down, stuck his cold fingers in the scruff of my neck, cheerfully called me “chick,” and continued running around the room.

He repeated this routine every time he ran into me. Apparently, he decided that he could play with me in this manner. I didn’t like it; I cowered from his cold fingers and tried to slip out of his reach and get closer to Mom. From that safe place, I finally scrutinized him with interest and surprise. It seemed to me that he resembled no one: aquiline nose, immense forehead, black curly hair, disobedient forelock, and slightly protruding front teeth. And his eyes—so striking, so shining, so dark, so completely dark! They looked at you intently and at the same time absently. He had in him a kind of extraordinary strength and at the same time some sort of incomprehensible helplessness. One could sense that this man had a superior and extraordinary mind, yet possessed a great deal of childish spontaneity.

Poems, conversations, arguments

Dau’s quick visits to Leningrad always brought joyful excitement to my family, and sometimes he took us all to a restaurant. Whenever Dau visited, Mom would ask him to recite poems. He would oblige willingly, without being coy or making any excuses. He recited in a loud singsong yet somewhat monotonous voice, as if intoxicated by the music of the poem. It’s interesting that, despite his feel for poetry and its rhythms, he didn’t like music at all. Music simply made no impression on him. Once, after listening to a violin being played, he said, “I wish some guy would chop up that box!”

And so he would begin to recite Nicolai Gumilyov, and the first stanzas of the poem “Gondla” would boom around the room:

The wedding cup has been drained dry,

The nuptial banquet devoured,

Why then do you sit, morose,

At the ceremonial feast of kings?

His recitation caused chills to run up and down my spine—the effect was extraordinarily powerful and breathtaking. One knew little about Gumilyov during the Soviet era. He had been executed in 1921 and was a forbidden poet, but Dau knew a lot of his poems by heart.

Dad would change the subject to physics, and attempt to question Dau about some physical phenomena. For example, why can an electron be considered both a particle and a wave? How is that possible? Dau, pleased, would click his tongue and declare, “The equations say so, and we must believe them!” His faith in mathematical computation was unshakable. To jolt us even further, he would add, “And do you know that sometimes it’s impossible to tell precisely where an electron is located?” Everything he said seemed so astonishing and incomprehensible. Of course, he wasn’t going to explain to us the uncertainty principle; he just enjoyed seeing the shocked expression on our faces.

Dau greatly enjoyed subjecting his interlocutors to embarrassment and was always brusque and straightforward in his judgments. He loved to argue, and from those arguments, he always emerged victorious; he always had the last word. Mom also was an inveterate arguer and would defend her point of view to the end. Arguments arose especially around the subject of love and of human relationships in general. Mom believed that love (any type of love, not just between a man and a woman) is measured by the extent of sacrifice one is willing to make for the sake of the beloved. Dau would shout, “Rubbish! Rubbish! Rubbish!” He wouldn’t acknowledge any sacrifice.

Dau’s parents

From Mom’s stories, I know how my grandfather and grandmother met. Grandpa David was an affluent petroleum engineer who lived and worked in Baku (in Azerbaijan). Already about 40 years old, he was an avowed bachelor with no plans to get married. That greatly distressed his parents, especially because he was the eldest son. Keeping their motives well hidden, they asked David to accompany his cousin Anna to Switzerland; he agreed. It happened that Anna was going abroad with her girlfriend, which sealed David’s fate: With the ardor of youth, he fell in love with the 29-year-old Lyuba [a familiar form of her name]. Throughout their marriage, until her death in 1941, he treated her with exceptional tenderness and love.

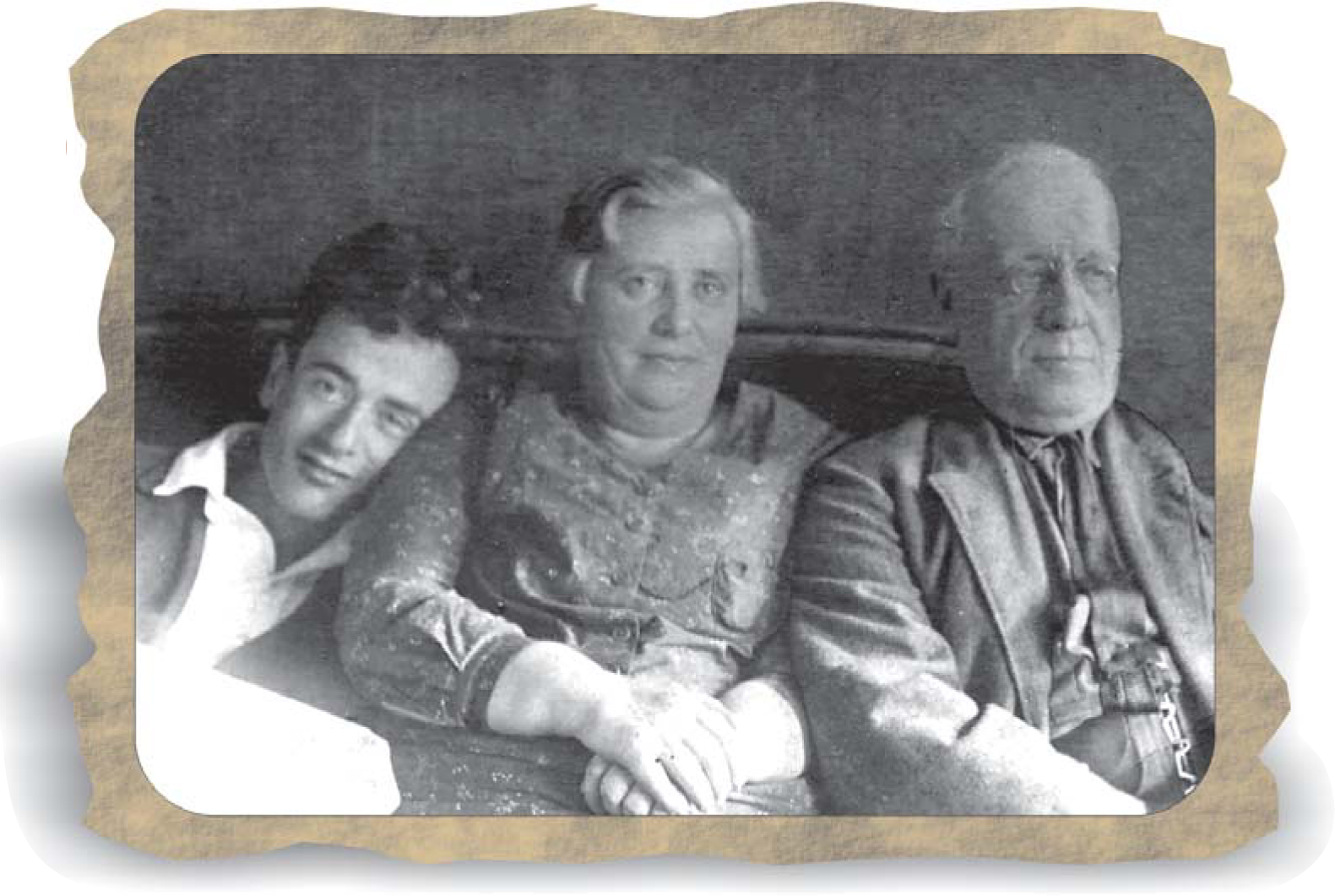

Lev’s parents, David and Lyubov Landau, in Baku circa 1904. (All photos are courtesy of the author.)

In her youth, Grandma Lyuba was quite beautiful. Dau inherited her intelligent and very dark eyes. In appearance and character, Grandpa was the complete opposite of Grandma. He was tall and bright eyed, with a handsomely masculine face. His entire appearance exuded importance. David and Lyuba were like ice and water: He was a composed and restrained person, and never raised his voice; she was a bundle of energy, quick-tempered and excitable. But opposites are often compatible and complement each other.

They married in 1905, and Grandma moved with Grandpa to Baku. Their daughter Sonya [the familiar name for my mother], was born on 8 August 1906, and their son Lyova, Uncle Dau, on 22 January 1908. My grandparents settled in a spacious six-room apartment in the center of town at the corner of Torgovaya and Krasnovodskaya Streets (today’s Samed Vurgun and Nizam Streets). A commemorative plaque there attests to Lev Landau’s birthplace.

Grandma devoted a great deal of time to raising her children. Sonya and Lyova became fluent in French and German, took lessons in gymnastics, and learned to play the piano, although neither of them had an ear for music or even liked it. Lyova was already then stubbornly literal: When the music called for forte, he played loud enough to shake the walls; when pianissimo, he played so softly that nothing was audible. From early childhood, Lyova displayed outstanding mathematical aptitude, so Grandma decided to release him from music studies. Sonya, however, studied music for 10 years and apparently did not play badly; but once she finished her schooling, she abruptly cast the music away and never again went near a piano. Because of that rejection of music, her father did not speak to her for a whole year. In sum, the little family was stubborn, and the children complicated.

Grandpa was a gifted mathematician from childhood, and graduated from school one year ahead of his peers. However, he won only a silver medal, rather than a gold one, as punishment for helping a classmate during an examination. With his young son, and later with me, he studied a lot—especially mathematics. That enabled Lyova to reveal early his exceptional mathematical talent.

After the Soviet takeover, the family was “compacted,” and outsiders took up residence in the Landau family’s apartment. The children went to Leningrad to study: Sonya at the Leningrad Technological Institute, Lyova at the University of Leningrad. At the beginning of the 1930s, Grandpa and Grandma moved to Leningrad and settled in the apartment of Grandpa’s sister, Maria.

Grandma Lyuba was an unusual person. Strong willed, purposeful, decisive, and energetic, she toiled all her life. Born into a very poor Jewish family, she became her own person through her hard work and talent. Having arrived in St. Petersburg in 1898, she obtained permission from the governor general to reside in the capital. Before the revolution, Jews needed such permission and could live only in certain quarters. She was extraordinarily industrious and, it seemed, could manage to do everything: She assisted in births, taught children in Jewish school, prepared frogs for scientific experimentation, wrote articles and books, lectured in the Medical Institute for Women (from which she herself had graduated), and made my dresses. I still have reprints of her article “On the Immunity of the Toad to Its Own Poison.” She also wrote, in 1927, A Short Guide to Experimental Pharmacology , which still offers an engaging and accessible explanation of the action of medications.

Not only could Grandma do everything, she also possessed an amazing pedagogical talent. One can definitely say that Dau’s outstanding personality and capacity for work were inherited from his mother. It’s a pity that Grandma didn’t live until 1946, when Dau was elected to be an academician. Grandma adored her son, understood his genius, and believed that, once he received recognition, all his quirks and eccentricities would be forgiven.

The arrest

The following leaflet served as the official reason for the simultaneous arrest, on 28 April 1938, of the three physicists: Lev Landau, Yuri B. Rumer, and Moisey A. Korets.

“WORKERS OF THE WORLD, UNITE!”

Comrades!

The great cause of the October Revolution is being despicably betrayed. The country is inundated with torrents of blood and filth. Millions of innocent people are being thrown into prisons and no-one can tell when his own turn will come.

It is clear, comrades, that the Stalinist clique has carried out a fascist coup. Socialism has remained only on the pages of the habitually lying newspapers. In his rabid hatred of genuine socialism, Stalin is not different from Hitler and Mussolini. Destroying the country for the sake of his own power, Stalin is turning it into an easy prey for the brutal German fascism.

The only way out for the working class and for all the toilers of our country is a struggle against Stalinist and Hitlerist fascism, a struggle for socialism.

Comrades, get organized! Don’t fear the NKVD [secret police] butchers! They are capable only of slaughtering defenseless prisoners, of catching unsuspecting innocents, of plundering national property, and of concocting absurd court trials for nonexistent plots….

The text of the leaflet is astonishing for the depth of the authors’ insight into the essence of the regime, as it took shape in 1938. One can detect Dau’s style, his conciseness, logic, and persuasiveness. The comparison of our system with fascism was one of his favorites. In precisely those words, he wiped out my own political illiteracy many years later. The lines in the leaflet are suffused with his naïve faith in socialism, typical of his early convictions.

Brother and sister, Lev and Sonya Landau, in Baku circa 1912.

I remember very well the turmoil of 1938. I was still too young (four-and-a-half years old) to understand what was going on. Dau’s soon-to-be wife, Kora, arrived unexpectedly at our house. She brought with her very bad news—so I sensed from my parents’ agitated conversation and from their distressed faces. Mom wept. The news was about Dau’s arrest. Immediately afterward, Kora escaped from Moscow, fearing that she too would be arrested.

After that, Mom started traveling to Moscow without notice and would return tired and upset. She would stand in long lines to learn anything about her brother; that too was not without its risks. When she finally reached the office of one of the NKVD’s directors, he asked her, “Why do you fuss about an enemy of the people? Go home and don’t show up here any more!” She tried to explain that Landau was a person of international fame and that the country might lose a prominent physicist and a scientist of the highest caliber. Meanwhile, knowing that one was allowed to send 50 rubles to every Soviet prisoner, Grandma was dispatching telegrams and money orders to all prisons, trying to discover in which prison her son languished.

Of course, Mom’s running around and Grandma’s money orders couldn’t free Dau. That was achieved by the efforts of the intrepid physicist Pyotr Leonidovich Kapitsa. At that time, few knew about it; at home, Kapitsa’s activities were mentioned only in whispers.

In 1991, the journal Izvestia TsK KPSS published material on Landau’s indictment for anti-Soviet activities, under the headline “Lev Landau: A Year in Prison.” A fierce debate emerged, and continues, as to whether Dau participated in the writing of the leaflet. In the transcript of the interrogation of 3 August 1938, Dau admitted, “At first I reacted negatively to this proposal and expressed fear that this form of action was too risky. At the same time, however, I agreed with Korets that political subversion of this sort might create a big impression and produce significant results.” The same archival file also contains a handwritten confession by Dau: “Korets wrote the leaflet of which, on the whole, I approved, after having made some comments separately.” In effect, then, he did not write the leaflet but just read it and added his comments. This he habitually did with almost all the Theoretical Physics textbooks—the collection of lectures and papers published jointly with Evgeny M. Lifshits and other physicists.

Nevertheless, the question arises: How could Dau, who regarded the leaflet idea as risky, agree to take part in it? I believe that, being quite perspicacious and witnessing his friends and coworkers being arrested, he understood clearly that he would not be spared for long. Despite his fear of what was coming, he decided to give early warning to others and announce loudly the impending danger, rather than go like a wretched lamb to the slaughter. If that’s indeed how it was, then more honor to him and more praise for his courage!

Dau and me

Lev Landau was not simply a person who was close and related to me, but also one who played a very big role in my life, in my choice of specialty, in shaping my character. From an early age, physics attracted me as the science capable of explaining the incomprehensible, of revealing the secret essence of physical phenomena. Without doubt, my desire to become a physicist was strengthened not only by my proclivity to the precise sciences, but also by my frequent association with Dau and by the aura of his fame. I graduated from high school with a gold medal, rushed immediately into university lectures, and never hesitated in my choice of profession. I wanted very much to enroll in the physics department of the University of Leningrad, but the time for that was extremely inopportune: In the spring of 1951, anti-Semitism in daily life and at the state level flourished with all its bright colors.

Dau, who was aware of the political atmosphere more than anyone, attempted to help me. Although he realized in advance the futility of such attempts, he approached several university physicists on my behalf, but to no avail. I had to bid farewell to my university dream. After I finally graduated in 1957 from the Leningrad Electrotechnical Institute in the field of semiconductor physics, I received from him this congratulation: “I don’t know how to write, so I’ll limit myself to wishing you all the best, and in particular success in love. Your dissolute Uncle Lyova.” Again he wrote, “My congratulations to Ellochka for her successful graduation, and best wishes for future progress” and “Dear friends, I am very happy that all ended satisfactorily for Ellochka, so that, in her person, we’ll now have my heiress. I warmly kiss and shake your hand, Lyova.” That last one was sent in 1958, when I was accepted for work at the Institute of Semiconductors, under Abram Fyodorovich Ioffe. And what a flattering inscription Dau wrote on my 1951 edition of his and Lifshits’s Statistical Physics : “To the future successor Ellochka, with the very best wishes—your dissolute Uncle Dau.” With the terms “heiress” and “successor,” he was flippantly ironic: He knew his own value too well to compare me to him.

As to issues concerning love, marriage, and children, Dau started to “educate” me when I was still a young girl. He preached to me his theory that one should acquire a lover at the age of 19 and get married to the third lover. How he could assert all that with such precision, I don’t know. I would blush, turn pale, plug my ears, and run away from him. But nothing could stop him. When I turned 19, he tormented me to such an extent that I found it necessary to invent a nonexistent lover so that finally he would let go of me. Today I understand that my conversations and arguments with him emancipated me, peeled off my girlish timidity and inhibitions.

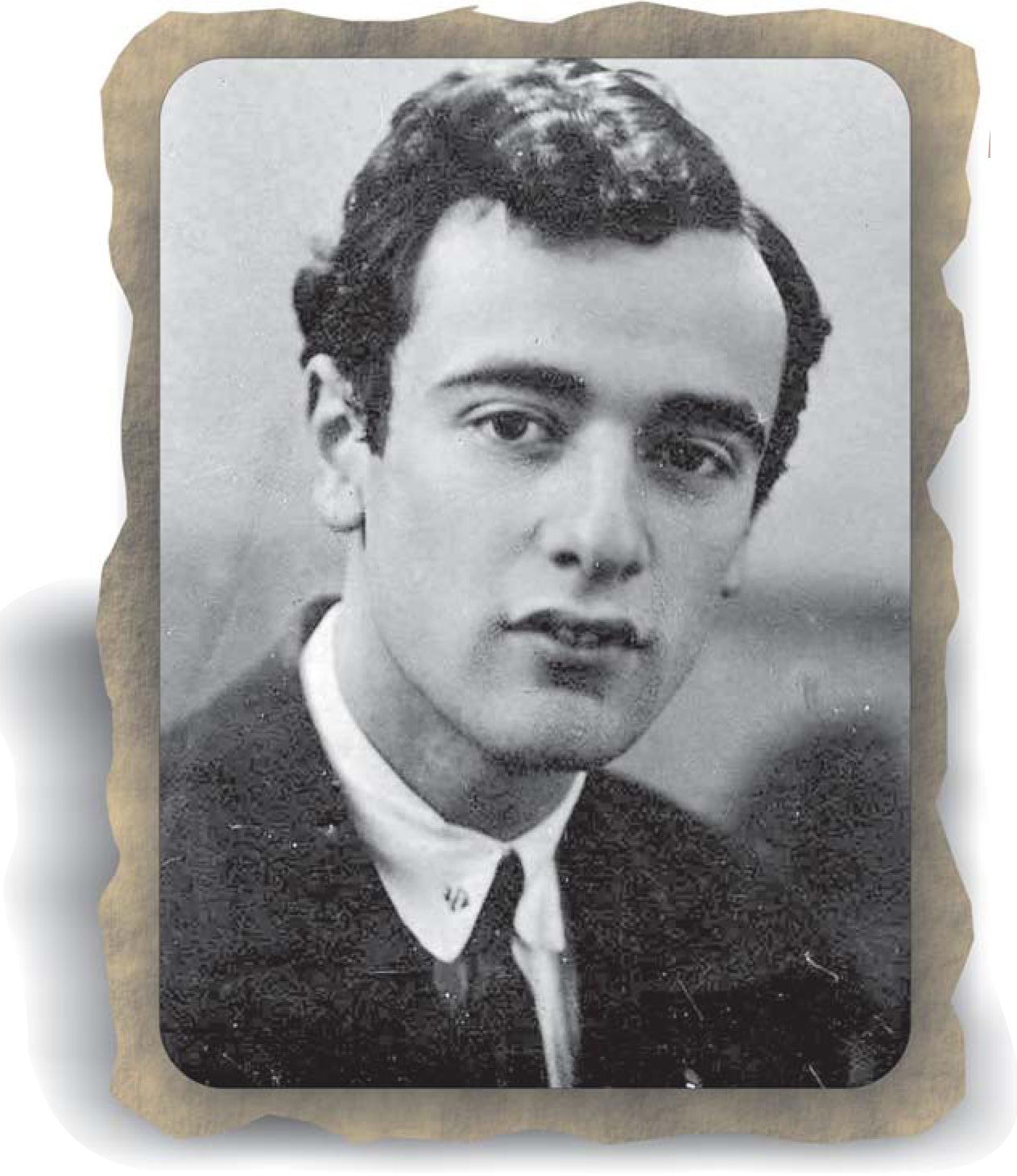

Lev Landau as he looked in the late 1920s.

When I was in the ninth grade, Dau decided to begin my political education. He often and with relish quoted Lenin: “One cannot be blamed for being born a slave, but a slave who shuns aspirations for freedom and who, moreover, justifies and glamorizes slavery, evokes legitimate feelings of indignation, contempt, and loathing—he is nothing but a lackey and a boor.” He wanted me to know the sort of country I was living in and what was going on around me, in defiance of the chronically mendacious official propaganda. He openly called our socialist system “fascistic.” I resisted, tried to object, and insisted that not everything was so terrible. But he explained to me that an enormous number of innocent people were being locked up in camps, and there was no end in sight. His lesson to me ended with “And Stalin is no less than the chief fascist.” Those revelations were all a shock to me; I was speechless, stunned. The educational conversations with Dau turned me into a new person; I began to look at many things differently, with open eyes.

Stalin’s death in 1953 led many of those around me into a state of pessimistic anticipation. Dau was the only one among those close to me who rejoiced openly. He repeated endlessly a line from Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya: “We shall yet see heaven studded with diamonds!”

Money matters

Dau was not stingy and was always glad to make people happy if all it took was money. However, he developed some strict rules and theories for managing his finances. For example, he would write down in percentages how he planned to allocate his expenditures. He allotted his wife 70% of all expenses (and not 60%, as Kora has claimed) for household necessities, leaving 30% for himself. Of his own share, he sent 10% to Mom, accompanied by the sweetest little messages.

I know that he also sent money to Rumer, who was in exile—and Rumer was not the only one. Dau set aside the rest of his share of the income for “debauchery,” as he called it. It basically went to pay for taxis, presents, and all sorts of trifles.

Lev Landau with his parents in Leningrad in the mid 1930s.

When Dau occasionally took Mom and me to a restaurant in Leningrad, he always checked the bill instantly, as soon as it touched his hand. If the bill was too high, he pointed out the error to the waiter and withheld the tip; he would tell us, “I don’t like to be swindled.” Otherwise, he didn’t skimp on tips.

Other interesting stories about Dau and money abound. For example, Kora bought a rug and put it in Dau’s study. She considered that purchase “debauchery” and demanded additional allowance for it, which Dau gave her. The rug lay in the study for a while, but then Kora took it away, claiming that their son, Garik, needed it to keep warm. But then Dau rebelled and demanded reimbursement. Good order should be maintained!

Dau, women, and family

Dau attached great significance to women and especially women’s beauty, but not as great as people were led to believe, or as implied by his own exaggerations. He classified them according to their looks (how can Dau exist without classification?): Women are either beautiful, pretty, or “interesting.” Plain-looking women belong, apparently, to the fourth and fifth classes: “Parents Should Be Reprimanded,” and “If They Do It Once More, They Will Be Shot.” While walking along the street, he would suddenly raise one to five fingers, indicating to his interlocutor the class to which a woman walking toward him belonged.

The classification was followed by theories, and the theories by practical implementation. Dau’s basic thesis was that a person should be happy and retain his personal freedom, no matter what it takes. His greatest fear was to lose his independence, and he often teased devoted husbands by calling them doormats. To all who cared to listen, he explained that marital infidelity is essential, because it results (so he believed) in a more durable marriage. He told me that few could boast of as long an attachment as his with Kora, and all because he followed his theory. For quite a long time Kora remained his only woman; but even then he kept telling her, “The basis of our marriage will be personal freedom.”

He engaged in endless conversations about women and love. But in reality, I believe, the fingers of two hands would suffice to count all his lovers. For the most part, they were not casual relationships but rather lasted for several, and sometimes many, years. But because he talked incessantly about women and propagandized all sorts of spousal infidelities, one would have thought that he was in the habit of changing lovers like gloves.

Dau had very small and helpless hands, hardly capable of holding a camera, and very smooth little palms. He said that they were made for caressing. Dau was convinced that all a woman needs is beauty (and, well, the talent not to be a “log of wood” in bed, to use his words), and all the rest was optional. In conformance with his theory, he chose Kora, who was indeed beautiful in her youth, as his life partner. Unfortunately, beauty gradually fades and then what is left? Dau and Kora did not have any common interests and, although I usually stayed with them during the winter holidays, I don’t recall their having any conversations apart from the most mundane daily discussions.

Dau’s family life demonstrated, I believe, that his theories, when applied to real life, led to deplorable results. It’s not surprising that, for more than six weeks, his wife did not visit him when he was in the hospital fighting for his life, and that she refused to contribute any money for his medications.

Dau’s work

During conversations, Dau’s eyes often became vacant, gazing past me somewhere into space. He would still keep talking, but then, as if forcing himself to speak, he would say in a colorless voice, “Go…. Go…. Later …,” at which point I would quickly retreat. I had the feeling that Dau disappeared somewhere with his thoughts and calculations, only to reappear from time to time. Sometimes, when visiting someone or just sitting with us, he would grab a scrap of paper, even a piece of newspaper, and start scribbling on it furiously.

In the morning, soon after breakfast, he would skip along to the institute, often without a coat (luckily he only had to cross the courtyard). In the afternoon, Lifshits would drop by Dau’s place, and from behind the study’s closed doors one could hear their loud arguments. After a couple of hours Lifshits would leave, agitated and red-faced.

Although it was not always apparent, Dau worked very hard—and demanded the same from others, especially his students. Paraphrasing the communist philosopher Friedrich Engels’s “Labor created a man out of a monkey,” Dau said repeatedly that if humans didn’t labor, they would again sprout tails and start climbing trees. I once heard him say to one of his graduate students, whom he considered lazy, “It seems you’ve already sprouted a tail.”

When a graduate student couldn’t decide on a topic for his dissertation, Dau would say to him, “I am a golden apple tree, but one must shake me to cause one of these golden apples to fall.” He believed that active conversations were needed before new ideas could form. Certainly, he had no equals among those around him, and he felt it necessary to associate and establish discourse with scientists in other countries, scientists of the same international caliber as his. The iron curtain completely excluded the possibility of such contacts: He was not permitted to go abroad, not even to friendly China. He considered that scientific solitude nothing but tragic.

Dau’s 50th birthday

Dau was despondent when he turned 50. But his friends and students had prepared something quite unusual. I went to Moscow on his birthday, 22 January 1958; Dau was happy to see me, but was unusually downcast. He didn’t want his 50th jubilee to be celebrated at all, let alone celebrated with the customary pompous laudatory speeches.

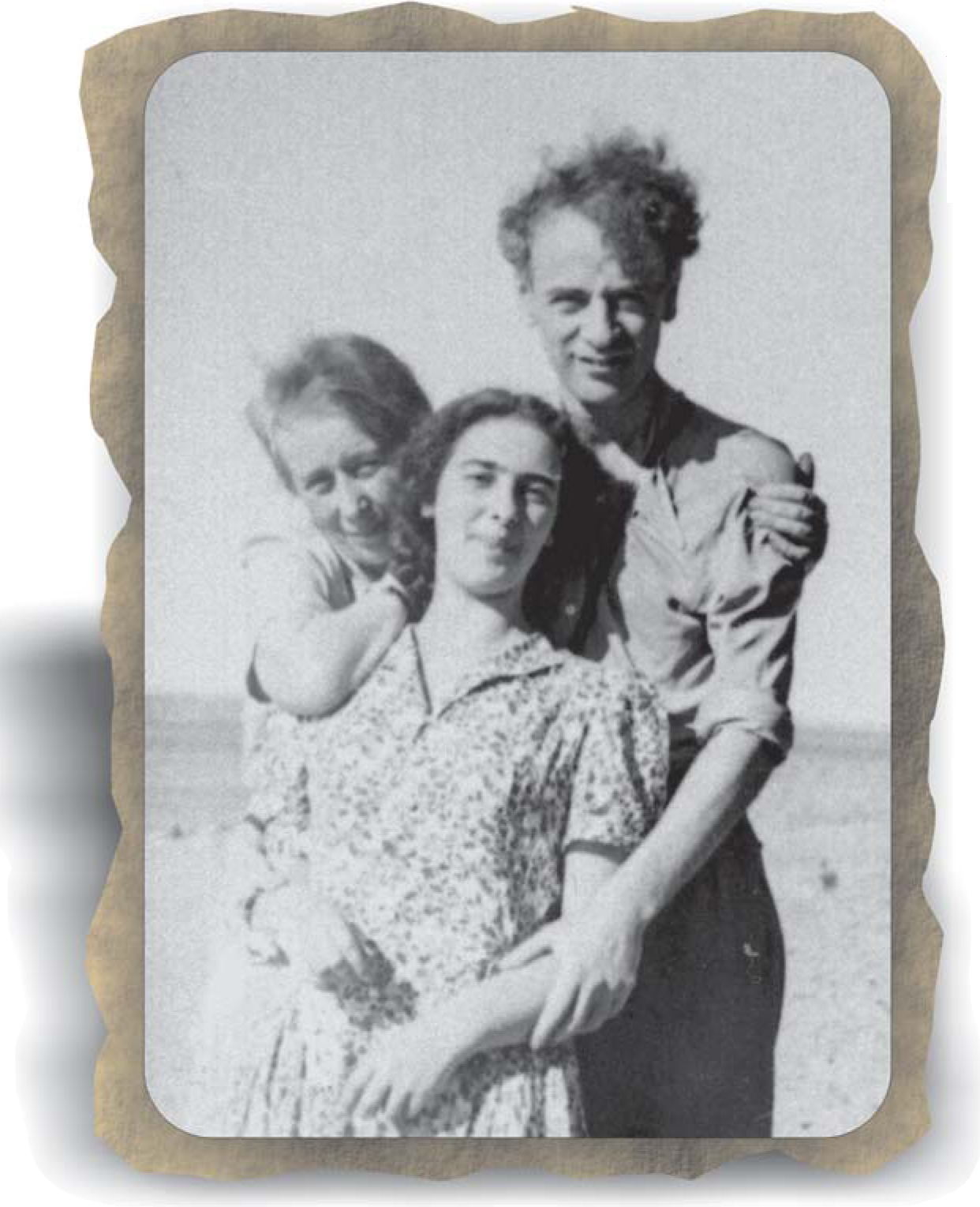

Lev Landau, his sister Sonya, and me in the center, at the shores of the Baltic Sea near Leningrad in 1950.

We left for the institute, where the celebration was to take place. As soon as we arrived, we felt the exhilarating and festive mood. A huge printed announcement, “Congratulatory speeches must be left in the checkroom,” pleased Dau greatly. The party’s atmosphere was so festive and informal that Dau cheered up in no time at all. Arkady Migdal, the master of ceremonies, opened by announcing that anyone using the expressions “the great physicist,” “the founder of the outstanding school of …,” and so forth, would be assessed a penalty. The well-wishers approached the rostrum and each in turn congratulated Dau. He would clink his wine glass with theirs and hand it to the “tippler” who stood beside him and dutifully drained its contents. Dau’s graduate students took turns performing this duty while wearing a drunkard’s red nose to identify their role.

It was clear that much time and effort were devoted to preparing the gifts, which exhibited a great deal of inventiveness and affection for the teacher. There was a satirical biography of Dau, written with great humor. There were marble tablets—like those given to Moses on Mount Sinai—on which 10 of Dau’s scientific results were engraved. One physicist brought a beautiful walking cane, for Dau to use to chastise apathetic students. Vladimir Levich brought a lion’s tail, which Dau merrily fastened to himself with small straps; then, showing off, Dau climbed on a chair and wagged his tail in front of everybody. There were a great many other presents, just as ingenious. Not a trace was left of Dau’s gloomy mood; he brightened up and enjoyed himself, as did everyone else. “Nobody ever had such an anniversary party!” he boasted.

Was Dau a coward?

Whenever Dau wanted to skirt a politically sensitive subject, he would say repeatedly, “I am a coward, I am a coward!” uttered with a humorous clownish intonation. It was impossible to comprehend what he was actually thinking and what he meant to imply.

The facts demonstrate that he was a freethinking person who understood perfectly well that he lived in a totalitarian state in which every free thought was repressed and every free thinker persecuted. Nevertheless, despite his distressing prison experience in 1938, Dau was daring enough to express straightforwardly and harshly his views about both science and politics. He wasn’t afraid of sharing his ideas—which were subversive for those days—even with me, then just a 16-year-old schoolgirl. He declared openly that the universe is finite, although that contradicted Marxist doctrine. There are many other examples of his boldness.

In the early 1950s, during his work on the atomic bomb project, he was assigned bodyguards. Some physicists considered it an honor and a token of preeminence, but Dau flatly refused the “hoodlums,” as he called them. Disobeying a KGB recommendation was a very risky act on his part. Lifshits made a special trip to Leningrad to ask Mom to talk sense into her brother. But Mom, and especially Dad, whose opinion Dau greatly respected, remained almost the only ones close to Dau who supported his stance. His decision to reject the bodyguards was unwavering; they never made their appearance, and Dau went on working. It should be noted that he found his work on the atomic bomb disagreeable and tried his best to reduce it to a minimum.

When Kapitsa refused to work on the atomic bomb, he was dismissed and banished to his dacha outside Moscow from 1946 to 1954. Dau was one of only a handful who defiantly, once a month, visited the disgraced scientist. To do so at that time required courage: When a person fell out of favor, it was normal to immediately ignore that person and even shun the individual’s family.

Here is another example: For many years, Dau had been assisting Rumer, who was arrested with him in 1938 and then exiled. Every month, Dau mailed him a money order; he did so openly and without trying to conceal it. I found out about it accidentally, when I witnessed the reunion of Dau with Rumer after the latter had returned from exile. If Dau indeed considered himself a coward, his actions only demonstrate how high he set the bar for himself.

The accident

On 7 January 1962, Dau had his calamitous car accident. He was traveling to my place in Dubna, worried about me. On 11 November 1961, he had written to my parents: “Dear friends, what’s going on with Elka? It may do her some good to seek my advice!” I had left my husband and found myself in a complicated situation. Dau knew about it, but not from me: I hadn’t phoned and hadn’t gone to Moscow. So he decided to come to Dubna, survey my circumstances, and perhaps help with his advice to disentangle the developing situation.

Finding out later that he intended to come, I phoned him in Moscow and asked him not to, trying to explain that his arrival would only aggravate the situation. He answered that he would think it over. When I realized by the next evening that he hadn’t arrived in Dubna, I decided that he hadn’t left Moscow. But, unfortunately, he was too stubborn.

Alas, on the slippery road, a frightful collision with a truck awaited him. As fate would have it, feeling hot, he had taken off his fur coat and cap, which might have cushioned the blow. Everybody else involved in the accident ended up with minor bruises and scratches: Even the eggs being taken to Dubna remained intact. But Dau suffered very serious fractures and other internal injuries.

The accident happened in the morning. The following day, having taken the first train from Dubna, I arrived in Moscow at hospital number 50. Alarmed physicists crowded the ground floor, organized watch shifts, went to meet the airplane that was flying in medications, brought doctors for consultation, and did everything else that they could. As the only relative present at the hospital, I was permitted upstairs to see him. I went, trying to calm my anxious heart and my trembling hands and legs. It was horrid. I understood that there was little hope. When I went downstairs, I was surrounded by the physicists, familiar and unfamiliar, with their questions and expressions of sympathy.

Through the tireless efforts of Sergey Nikolayevitch Fyodorov and other doctors, and in defiance of all the terrible prognoses and predictions, Dau started to gradually return to life. Following Mom’s request, nurses and aides from the hospital wrote her in Leningrad about Dau’s condition. Consciousness finally returned and Dau recovered his power of speech.

I still have the rough draft of Mom’s letter to Dr. Fyodorov, who spent six consecutive days and nights with Dau, rescuing him from death’s clutches. In that letter, Mom provided an accurate and, I would say, insightful characterization of Dau, with whom she had been linked since childhood, not only through close kinship but also through tight spiritual bonds. Among other things, she wrote the following:

Despite the fact that we live in different cities, no one knows him better than I do, and, perhaps, in certain respects I am closer to him than his friends and other relations, as he is one of those people whose interior is highly insulated despite a very gregarious exterior. Despite his celebrity and the eccentricities for which he is famous, he is a very shy person. Although he is one of those persons who is very passive and impractical, he hates to be given orders and directions. He likes clarity in all issues; he is not inclined toward sentimentalism—in fact he despises it; and he dislikes being pitied.

At the end of February, when it became clear that Dau would live, Kora at last appeared in the hospital and took matters into her own hands. In March, Dau was transferred to the Burdenko Institute of Neurosurgery, which Kora hated. She decided to have Dau transferred, at any cost, to the hospital of the Academy of Science. That hospital provided excellent care, but it lacked the top-notch specialists that Dau needed and who could, perhaps, have helped his further recovery.

I came from Dubna to visit him. We strolled in the garden. His memory for events in the remote past still functioned beautifully. As in the old days, we recited poems together. I would start a stanza and he, right away and by heart, would take over. We recited what he loved most—poems by Konstantin Simonov, Nikolai Nekrasov, and Gumilyov. It was difficult to converse with him. Sometimes he said, “I don’t feel well today. Come tomorrow.” At more lucid moments, he acted as if he recognized his condition and said, “I’ll certainly not be able to engage in theoretical physics right now; instead, I’ll start with mathematics.” He showed no interest in me and my concerns, and nothing remained of that “jolly Dauka,” as he used to dub himself.

The funeral was a solemn affair, full of everything that Dau disliked—flowers, music, and pompous speeches.

Dau had been staying in the academy hospital for more than nine months. His condition remained the same, but Kora refused categorically to take him home. Of greatest concern was the fact that Dau couldn’t associate with other physicists, and Mom believed that such association was essential to his recovery. My parents decided that if Kora wouldn’t take him, then they would.

Finally, after being pressured by the academy’s administration, Kora felt compelled to take Dau home. There, she treated him affectionately and fed him well, but did her best to drive away physicists and anyone else who wished to see him. I continued to travel from Dubna, would sit with him an hour or two, and then travel back. There was no change in his condition; it was terribly sad.

The last time I saw Dau was on his 60th birthday, 22 January 1968. He was dispirited. I don’t believe he understood very well the significance of the date.

I didn’t see him again. Mom kept visiting the hospital where he was eventually hospitalized for intestinal obstruction and where he died on 1 April 1968. The funeral was a solemn affair, full of everything that Dau disliked—flowers, music, and pompous speeches.

[Editor’s Note: The full, unedited memoir from which this article was excerpted is available to subscribers at www.physicstoday.org

More about the authors

Ella Ryndina, an experimental physicist, worked in Leningrad from 1953 to 1960 at the Institute of Semiconductors, headed by Abram F. Ioffe. She then worked at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, near Moscow, where she received her PhD in 1969. She now lives in St. Petersburg, Russia, and can be reached at ryndin@RR3308.spb.edu

Ella Ryndina, 1 Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna, Moscow .

Arthur Gill, 2 University of California, Berkeley, US .