An Excursion with Enrico Fermi, 14 July 1954

DOI: 10.1063/1.1496375

Perched on a slope beneath the towering aiguilles of the French Alps, the Summer School at Les Houches commands a captivating view of the valley of Chamonix. It was a hardworking school, however, particularly in its early years, and enjoyment of the scenery was confined to brief intervals between lectures held in a recently converted barn. In 1954, the two months of lectures featured a course by Enrico Fermi on pion–nucleon interactions, and several other courses by faculty including Léon van Hove, Freeman Dyson, Robert Marshak, and me.

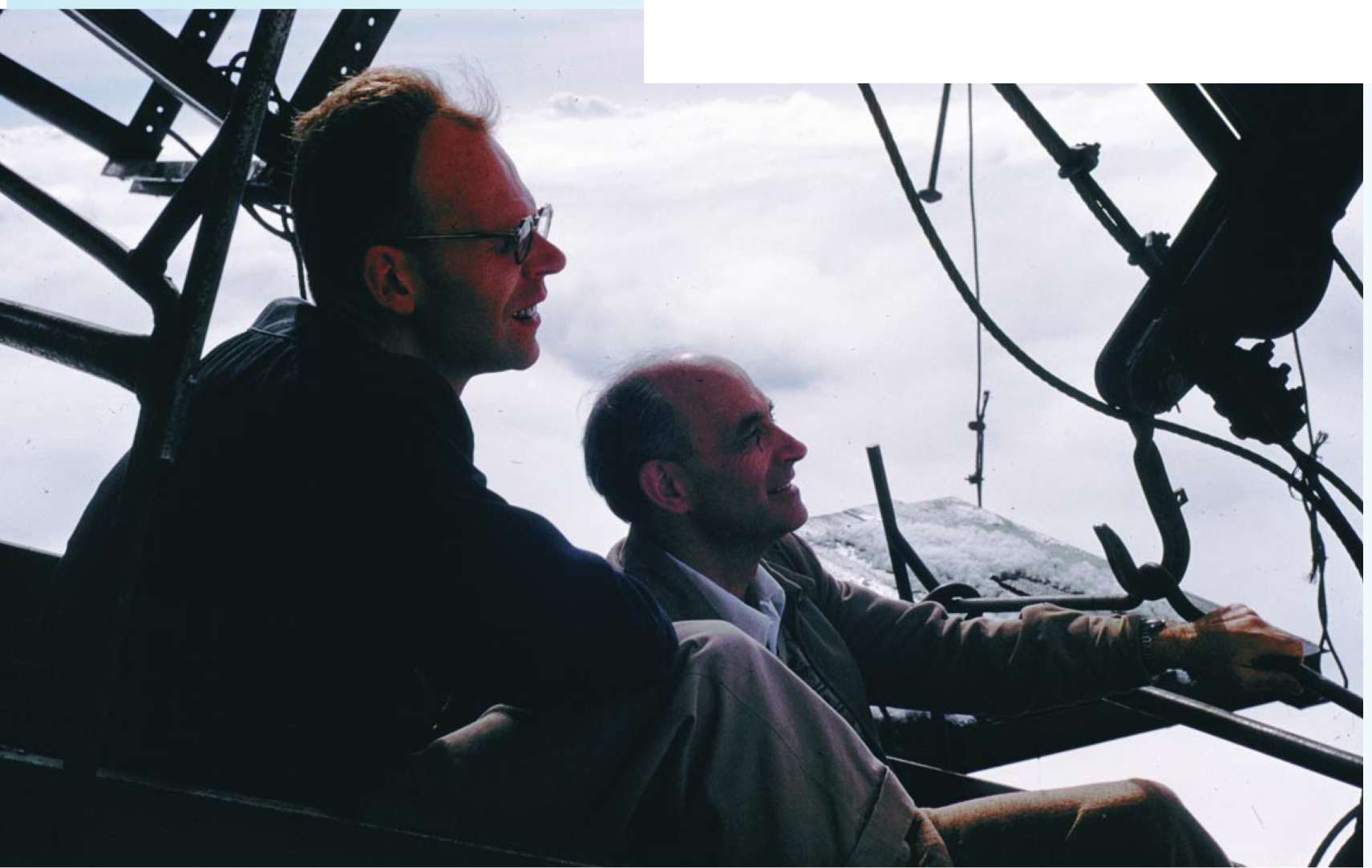

The second stage of the ascent. Fermi and van Hove gaze at the nearby Glacier des Bossons.

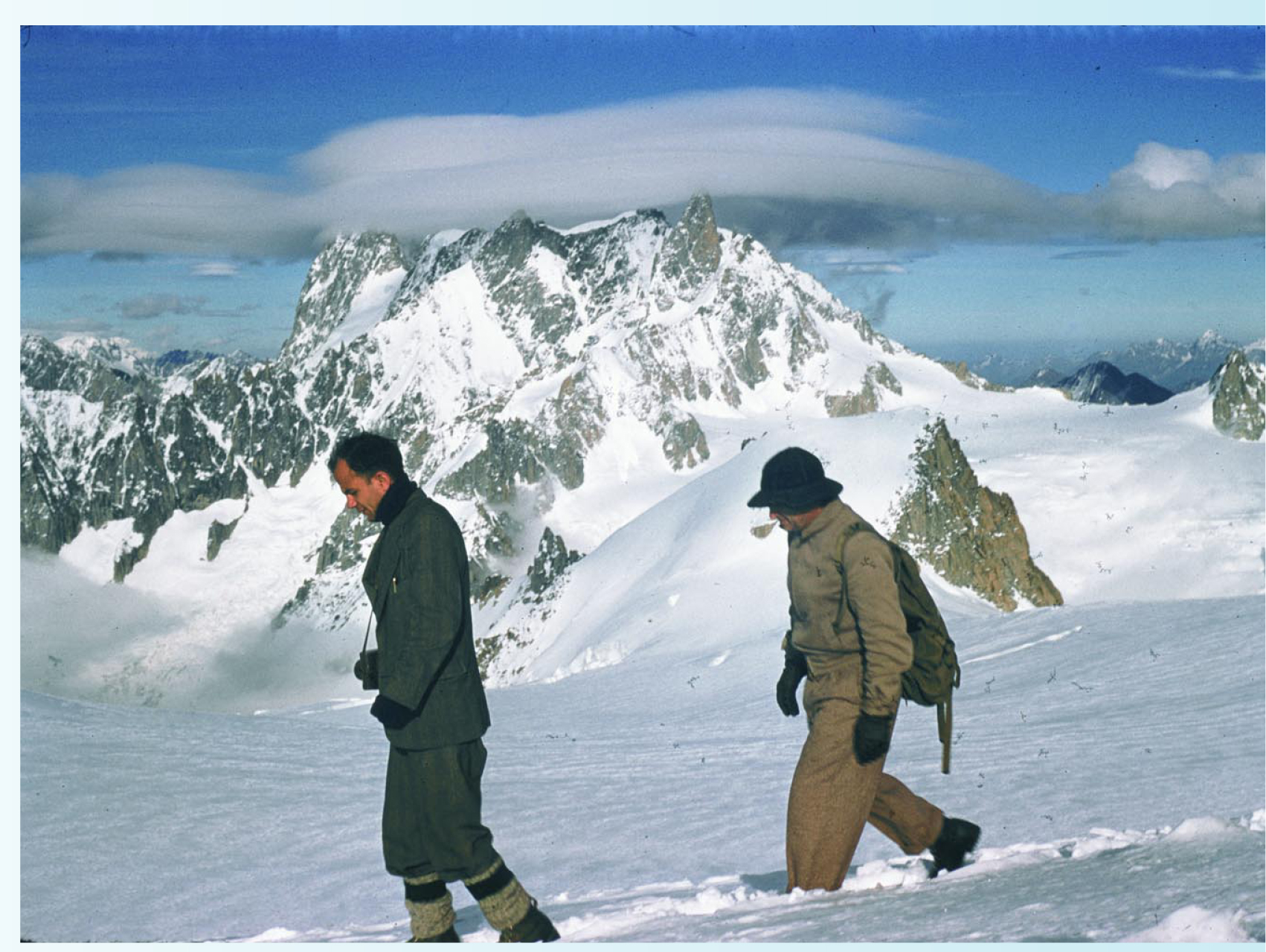

(All photographs are courtesy of Roy Glauber.)

The school’s director and founder, Cécile De Witt, scheduled a welcome respite from classes for the quatorze juillet holiday and suggested various excursions for the day. As one excursion, she negotiated for Fermi and three others of us a rarely granted invitation to visit the cosmic-ray laboratory maintained by the Ecole Polytechnique near the peak of the Aiguille du Midi. It was an exciting prospect, though its safety raised some questions. The great cable car system that takes tourists up to the Col du Midi was only in the earliest stages of construction in those days. We were to make the ascent, not in enclosed cars over two vast spans of cable as present visitors do, but in four stages on whatever cable conveyances were used to transport materials or workers for the construction project. And one of those conveyances had flipped over the year before, killing two workers.

van Hove after dismounting from the rudimentary second-stage conveyance.

Besides Fermi, our party of four consisted of van Hove, a student from Egypt, Afaf Sabry, and me—as official photographer. We arrived at the foot of the mountain in the early afternoon and were not altogether surprised to be asked by an attendant to sign accident indemnity waivers before boarding the first of our four conveyances. It was the decaying remains of a cable car that must have been run for tourists generations earlier. Fermi gazed heavenward and hoped out loud that the cable was in better shape than the car. Fortunately, it only mounted to the foot of the great hanging Glacier des Bossons.

Ready for takeoff in the third-stage benne just below cloud level. From left: Sabry, van Hove, and Fermi.

The next stage of our ascent was much more exposed and exciting. It required us to sit on what was little more than a broad plank suspended from the cable wheels by simple hooks at both ends. Someone was providentially awaiting us on the wooden platform to which the plank transported us. His task was to give us instructions for the next two stages, in which we were to travel in bennes. Properly translated, bennes means buckets; these were in fact shallow steel bins, also suspended from the cable wheels by two simple hooks.

Our benne seemed sturdier than the plank we had ridden earlier and, squeezed together in it we soon rose into a dense layer of stratus cloud. We were engulfed by glaring white fog and our world closed in to the benne beneath us and the squeaking of the wheels, unseen above us. Fermi smiled archly, saying he understood now how angels felt. He began singing the only hymn he knew: “Mine eyes have seen the glory… .” We all joined the chorus, “Glory, glory, hallelujah. …” It took only one repeat of the chorus to bring us out into clear daylight and our approach to the next platform, which projected from a cliff, well above the clouds.

Arrival at the third-stage platform. Van Hove and Fermi appear grateful for deliverance from the clouds below.

Another empty benne awaited us at this third and unmanned station, but boarding it posed a problem. As each of us entered and weighed it down, it sank another foot below the platform level. And as the last to board, I had to take an awkward leap that made the benne bounce ominously. There remained the question of how the benne would be set in motion. Our instruction at the earlier level had been to bang on the cable with a shoe. Fermi was happy to oblige with his boot, and that signal, evidently audible to someone at the top station, set us in motion for the final leg.

Sabry and Fermi on the Trek to the cosmic-ray laboratory.

We were greeted at the top by a physicist who led us on a 15-minute march to the laboratory through steeply pitched snow fields. The cabin was built on a high margin of the snow fields where they meet the great rocky escarpment of one of the peaks. I’d have to admit that visiting the laboratory itself, after our adventures in reaching there, was a bit of an anticlimax; we had all seen cloud chamber equipment before. But the cabin was warm, its veranda commanded an incredible view, and a glass of mulled wine at that altitude is a heady experience. The sun was lower in the sky as we trekked back to the top station. We had a brief wait for the next benne, which provided the opportunity to take a more leisurely photo of Fermi (see the cover of this issue). The trip back down the mountain afforded us a dizzying view of the valley below, but was somehow less exciting than the ascent. It even felt less perilous.

Two other trekkers, one of them the well-known Alpinist Gaston Rebuffat, head for the laboratory cabin shown in the upper right of the photo.

Fermi was vigorously active at Les Houches, participating in long weekend hikes. That made it all the more of a shock to hear of his complaining at Varenna, just weeks later, of the illness that led to his death in a matter of months. It was even more shocking given my recollection of an exchange with him in early July. He had been looking forward to hiking in the mountains and felt, as I did, that we had better find ourselves some appropriate boots. He drove me to Chamonix, and in one of the larger equipment stores there, a salesman showed us a vast selection of boots. My own interest settled on the sturdiest ones they had, inevitably the most expensive. Fermi, on the other hand, undeterred by their obvious weaknesses, bought the least expensive ones in the store. It was an odd contrast, and I teased him about it. His response was, “Well, you’re younger than I am, and you’ll be using yours a lot longer than I’ll be using mine.” That pragmatic thought—or was it premonition?—had already echoed in my mind before our mountain trip, and it has haunted me for years since.

More about the authors

Roy Glauber is Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Roy Glauber, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, US .