Writing the record of scientific knowledge

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4167

The Wikipedia entry for Physics Today states that the esteemed publication you are currently reading is “scientifically rigorous and up to date.” However, the entry explains, the magazine “is not a true scholarly journal in the sense of being a primary vehicle for communicating new results.”

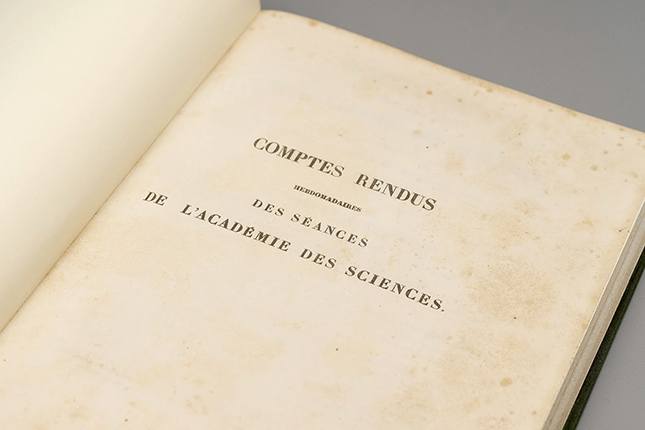

COURTESY OF AARON AUYEUNG/NIELS BOHR LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES WENNER COLLECTION

The careful inclusion of that distinction points to some important assumptions about what constitutes a “true” scientific journal. As historian of science Alex Csiszar observes in the introduction to his book The Scientific Journal: Authorship and the Politics of Knowledge in the Nineteenth Century, readers expect a great deal of those periodicals. They are “both permanent archive and breaking news, both a public repository and the exclusive dominion of experts, both a complete record and a painstakingly vetted selection.” Csiszar’s book explores how the scientific journal came to embody those apparent contradictions and demonstrates why we have made that particular medium the preeminent mode of communicating claims to knowledge.

Tempting as it is to draw a direct line between the establishment of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1665 and the 21st-century peer-reviewed scientific journal, recent historical scholarship has increasingly shown that the narrative is far more complicated. The rise of the scientific journal was the result of the interplay of political and commercial forces in post-Enlightenment Europe. Csiszar meticulously traces the development of journals in Britain and France during the 19th century, and he shows that shifting and competing ideas about scientific audiences and authors led to significant changes in the way scientific researchers engaged with print.

At the beginning of the 19th century, academies and learned societies were the most influential arbiters of scientific authority. Publication was not considered necessary for the establishment of a scientific reputation; in fact, the idea of putting scientific work in print could be viewed with deep suspicion, if not outright hostility. Journalism carried the taint of commercial opportunism, a problem when the ideal scientific practitioner was supposed to be disinterested in compensation.

But as publications dedicated to scientific subjects, produced mostly by entrepreneurial publishers, began to proliferate in the wake of the French Revolution, learned societies and academies sought to maintain their sway over scientific legitimacy by going into print themselves. The scientific journal as we would now recognize it took shape in the course of debates over questions of who could write about science, who could claim intellectual property rights, and who should be able to access scientific writings.

The great strength of Csiszar’s book is how it challenges both historians and scientists to confront the ways in which formats and genres of communication shape modes of inquiry. Our understanding of the history of scientific priority is considerably enriched when we pay close attention to the media through which claims to “discovery” were made. Similarly, modern scientific careers are shaped by the pressure to publish in certain journals, and that pressure influences the kinds of research scientists undertake. Csiszar asks us to imagine a world in which scientists were expected to write “a longer book that synthesized a field of information based on their own and others’ research,” an intriguing counterfactual that invites speculation as to how different the academic landscape would be.

The book’s comparison between France and Britain is particularly instructive and sets The Scientific Journal apart from much of the existing scholarship on 19th-century scientific periodicals, which has tended to be Anglocentric. Highlighting the differences between the two countries during that period shows us that the journal’s development and current form were far from inevitable. For example, referee systems in Britain and the US were initially exceptions rather than the rule. Meanwhile, the dominant journal in France, Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, employed no such system. Not until the second half of the 20th century did peer review become an internationally widespread method of judging potential publications.

The book concludes with a brief coda reflecting on the present, in which alternative formats made possible by the internet are challenging the apparent dominance of the scientific journal. However, Csiszar insists that those new platforms are subject to the same entanglement of scientific, political, and economic considerations as the supposedly antiquated print media they are purported to supersede. Technology alone cannot render knowledge “free” or “transparent,” he argues, and in order to chart a new future for the scientific journal, it will be important to understand its history. Csiszar’s book is an excellent example of how that history should be done.

More about the authors

Historian Matthew Wale completed his PhD at the University of Leicester. He is currently working on a project about 19th-century science periodicals.

Matthew Wale, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.